Written by: Jan Lumholdt

29.01.26

The ninth annual Film Policy Summit addressed some pressing issues within an industry and art form, currently in a dire state.

Cinema and politics, together and apart, are at the forefront at the Film Policy Summit, a regular programme item at the Göteborg Film Festival since 2018 and a useful annual navigation tool for a new year in Swedish film and its current state. The ninth edition, held January 23, gathered 200 professionals from all strands of the national industry, and presented 30 speakers, primarily political and public representatives as well as international participants. Arriving from France was Gaëtan Bruel, president of France’s National Film Board (CNC), and from Denmark and Norway, the film institute CEOs Tine Fischer (DFI) and Kjersti Mo (NFI) were along, bringing food for thought from their respective corners of Europe.

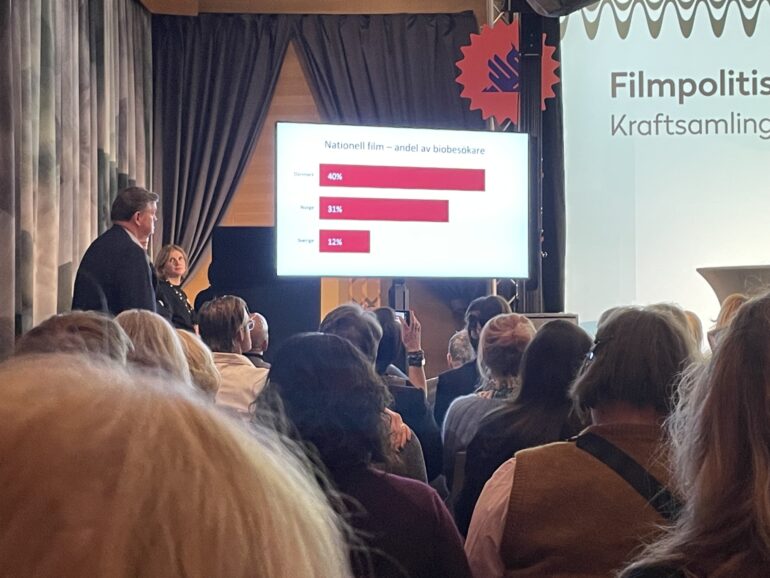

This year’s headline read “Kraftsamling för den svenska filmen” – ”Gathering Strength for Swedish Film” – another chapter in a lengthy chronicle where insufficient public financing, dwindling ticket sales and a concrete film law currently up in the air are among the stumbling blocks. In a debate article, published January 19 in Dagens Nyheter, CEO of the Swedish Film Institute (SFI) Anna Croneman, does not mince words, bringing a sharp warning of letting “Swedish film become a parenthesis in our cultural history” if certain pressing issues aren’t dealt with. Governmental funding hasn’t increased since 2006, pushing SFI to reduce its staff by almost a fifth in recent years. Comparisons with the Danish and Norwegian colleagues speak a clear and dire language: here, Sweden receives close to half the public funding of its neighbours. “Denmark invests approximately 215 SEK per inhabitant in its film policy, while the corresponding figure in Sweden (a country with almost twice as many inhabitants), is 60 SEK per person. Many representatives from international film organisations wonder how this has been possible,” says Croneman.

Representing that international bastion most often regarded as the strong champion of cinema as an artform and practising strict cultural regulation, this year’s keynote speaker Gaëtan Bruel started his presentation assuring that “the French model is not a miracle”.

“The design of the French system of support for cinema was not born at a moment of confidence, but at a moment of great fragility. In 1946, France signed agreements with the US, which was seen as a deeply destabilising moment, given that French cinema emerged from the war weakened and structurally vulnerable. Very quickly, the fundamental challenge was Hollywood studios, and now global platforms. The French response has never been isolation or closed borders. Instead, it was the conviction that cinema is both an art and an industry.”

The subject of the global streaming platforms and the implementation of various forms of streaming fees/taxes and/or reinvestment models – currently in effect in 16 European countries, Sweden not among them – was addressed throughout the summit. No clear stance on the issue was taken among the present political representatives, rather one of watch-and-wait caution – “caution” being the main keyword according to many, on the state of the current “Swedish Model”.

“Up in the air” can also be said to apply to said current state. Last year’s governmental film inquiry, presented March, 2025 and generally favourably received within the industry, has yet to be turned into a new film law, announced, but not yet finalised by the current government.

2026 being an election year adds further pressure, and several leading politicians from the current opposition, notably Amanda Lind of the Green Party and Nooshi Dadgostar of the Left Party, were in the room, advocating for urgent action. Not in the room, noticeably and regrettably, was the current Minister of Culture, Parisa Liljestrand.

Close to the end of this full day of expectant strength-gathering, the aforementioned film institute leaders Croneman of Sweden, Fischer of Denmark and Mo of Norway took the stage under the caption “Scandinavian contrasts in unruly times”, bringing forward many of the by now well-known dissimilarities. In the panel was also Mogens Jensen, previous Minister of Nordic Cooperation in Denmark, who aired that very national expression of trust and calm optimism: “Det ska' nok gå altsammen” – “It’ll fall into place, very likely all of it”.

True or false, the tenth Film Policy Summit, come January 2027, should – very likely – be most interesting.