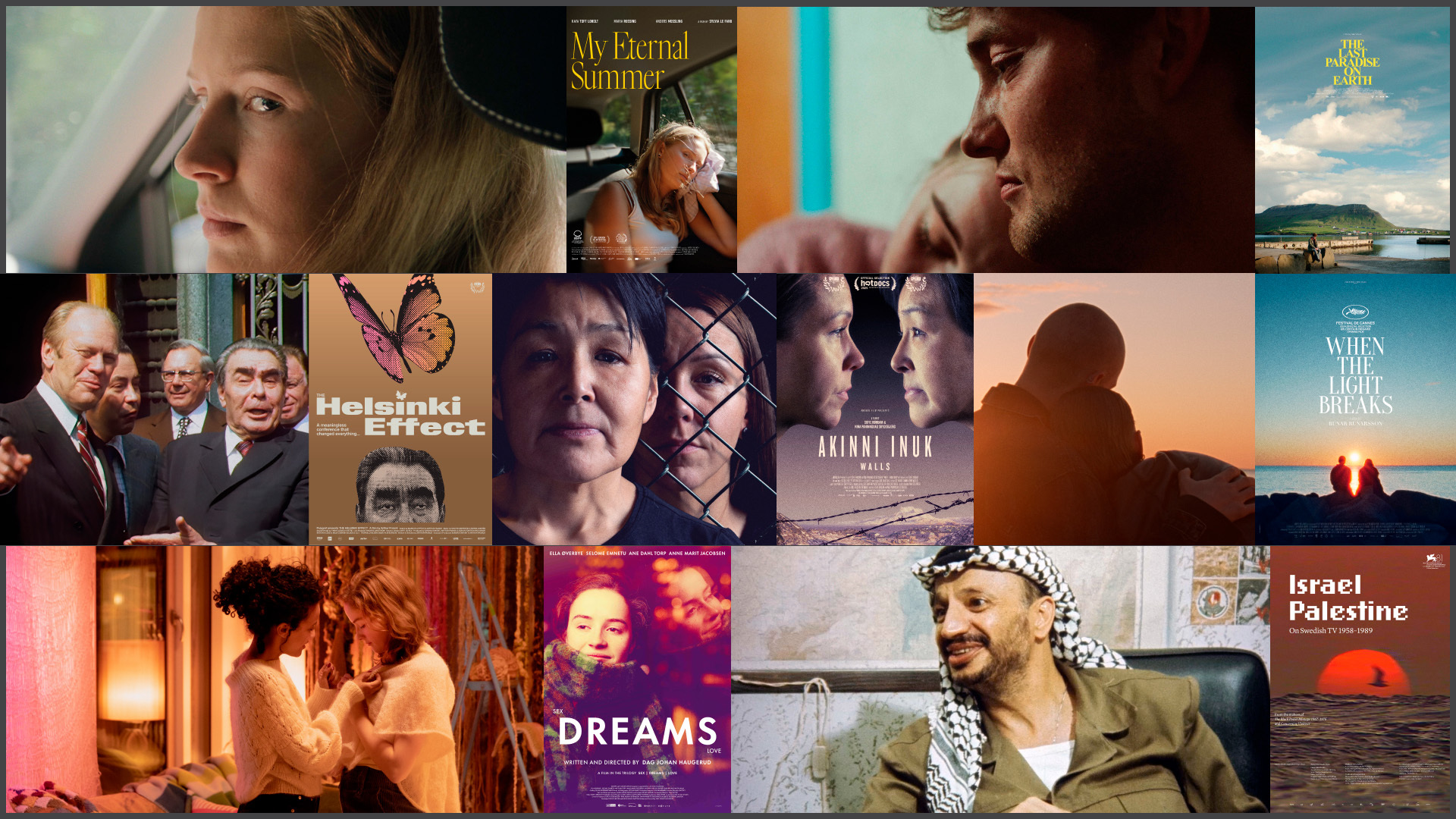

Seven exceptional films nominated for the 2025 Nordic Council Film Prize

First-ever nomination from the Faroe Islands – and a landmark year for Nordic documentaries.

The two directors talk about how their documentary WALLS – Akinni Inuk was filmed in a prison, how its main character Ruth was selected, and why one of them ended up in front of the camera too.

The Danish director Sofie Rørdam, the Greenlandic director Nina Paninnguaq Skydsbjerg and the Greenlandic producer Emile Hertling Péronard are nominated by the Greenlandic jury for the Nordic Council Film Prize 2025 for their documentary WALLS - Akinni Inuk.

WALLS - Akinni Inuk explores how two Greenlandic women are united by a shared traumatic past and a chaotic present. Ruth has spent almost half her life in prison and the last 12 years in indefinite detention, and Nina is working on a prison film project. The two women start seeing each other in the prison, and soon they develop a a deep friendship. The documentary also reveals the legal deficiencies of the Danish and Greenlandic prison system – a system that has trapped Ruth for half her life. WALLS - Akinni Inuk is a story about love, human empathy, hope and the struggle for a second chance.

What was the first impulse to make this film?

Sofie: After several years in Asia, where I worked with film, human rights, and legal systems, I returned home, only to continue to Greenland, where I was introduced to their unique correctional system. The system is built on the ideology of resocialisation, and the concept of “punishment” is not mentioned in the legislation. I was fascinated by the philosophy, and wanted to portray this story. However, the inmates’ reality nuanced the picture. The ideology looked better on paper than the daily reality of most of the inmates.

The correctional system in Greenland was created with inspiration from the small settlements where reintegration was essential for the survival of the community. However, today’s reality and criminality picture are far more complex, and life behind the walls are for many inmates very different and far more closed than the original intention of the law and penal system. My project took a new direction when the inmates themselves began filming their lives. The raw footage was full of creativity and honesty, and gave an authentic voice to those behind the walls.

Can you expand on how Ruth became the main character in the documentary?

Sofie: Ruth touched us with her deep and thoughtful manner. She was also the only one among the women with an indefinite sentence. While all the others knew their release date, Ruth had no grasp of a future. When we met her, she had served a 5 year sentence earlier, and 9 years of the custodial sentence. She had started to believe that she would never get out.

The prison was not built for inmates in Ruth’s situation. Normally, inmates with custodial sentences were sent to Denmark to serve their time, as the prisons there have different facilities for this. But as she was the only woman with this sentence, she was sent to serve in Greenland. I started looking into her case files, and also realised the tragedy of her fate and how she now seemed stuck in this system – and trapped in a legal limbo between Greenland and Denmark.

Nina: Whenever you do this kind of projects, it’s never about what you want to do. It is about collaboration, especially in an arrangement as vulnerable as a correction facility. We were very much focused on not telling people who should be our partner, but we realised who was taking to the camera and having an opinion. When we talk about matters like criminality, many people have images in their heads regarding the way people look, and when we’re talking about something as violent as killing or committing murder, many picture the perpetrators as men. I never got that sort of vibe with Ruth, and that changed my own perspective. You can never tell who someone is before you talk to them, and better still: listen to them.

I’m drawn to people who create a lot of questions in me. When I look into people’s eyes, which are the mirror of one’s soul, I can always spot the pain. It was a really beautiful way to connect through pain. It is raw and meaningful to connect through pain. The more Ruth and I talked, the more we realised that we were not that different, really. I am a very abstract person. I have too many questions, and she had this way of making issues simple. I could expand her boxes, or take away their box shape.

How involved was Ruth in making the final film?

Sofie: We kept Ruth updated regarding the process, but she was not involved in the making of the film. Ruth had just been released from prison after all in all 18 years, and this was a very sensitive time for her. She needed to feel safe. To come forward with her story through the film was a very brave and strong decision. Ruth’s strong wish was always that she could help others and be a voice for other inmates with the film. That others would not have to go through what she did. Nina watched the rough cut together with Ruth a couple of times, so Ruth could come up with her inputs and corrections.

The core of what made it possible was that she knew she had Nina by her side, that they would walk this path and put themselves out there together. Emile has obviously been a huge support, a clever guide and problem solver throughout the process as well.

What were the challenges when filming in a prison?

Sofie: We obviously had a lot of restrictions. And in the end the cameras were confiscated by the Prison and Probation Service due to security. But it was a unique opportunity and a tool for the inmates. In a prison where you’re stripped of your identity and freedom, the cameras also served as a therapeutic tool, claiming parts of your identity back by telling your own story. Before the cameras were confiscated, the initial plan was to do a series of workshops too, so they could develop their skills in filmmaking and other creative fields.

We also do understand that the process with the inmates having cameras was very delicate from a safety perspective, and we are thankful that we had the opportunity in the first place.

Nina was originally attached as a producer to the project. How did she end up in front of the camera, and as one of the directors?

Sofie: I feel it was a natural process that didn’t come as a big shift. At first, when the cameras were confiscated, we didn’t know how to proceed with the project. I was in Denmark then, and to keep the project somewhat alive and keep up the contact with Ruth, I asked Nina to visit Ruth equipped with some questions and a camera. To set up and record their conversation. Afterwards she would send it to me without watching it herself. In the beginning I would just look for Ruth’s answers, but slowly I began to observe what was happening between Ruth and Nina. Slowly Nina began giving a lot more of herself, and not just questioning Ruth.

Especially when Nina’s mother passed away and she started to find solace in Ruth, I would see sides of Nina that I never knew of. I also saw the enormous gift her presence and mirroring was to Ruth. It was very special and beautiful to watch a friendship unfold in the most unlikely way. After a while, Nina was so entangled in the story that she gave her producer role over to Emile.

Nina, as a director, how did you experience being in front of the camera?

Nina: As I started off as a producer, it was never my plan to be a director. It was just the easiest way, since I was in Greenland. It would have felt wrong to just turn on a camera and then sit behind it. It was a choice of safety to put myself on the line. When you want to tell these stories, it is kind of brutal to ask people to share their lives without being willing to do the same. Then it changed from an interview kind of talk into a conversation. It would have been unnatural for me not to answer her questions. I got sucked into the story by her presence and her raw honesty, which was something I have never come across before. Being able to talk about pain in such an unfiltered way was such a life lesson.

Sofie, what was it like directing your co-director?

Sofie: I very much just let Nina stay in her role as Nina. I let her go through her personal process of grief and healing and her friendship with Ruth, so that she could just be there, human to human, and not have the film in mind.

By Nina’s own wish, she never watched any of the footage during those years, so as not to become too self-aware in front of the camera. And she never sat in the editing room neither, as this was too hard. She gave us her complete trust. This project has required full trust among us all.

Which themes became most important for you during the process, and why?

Sofie: Punishment, justice and forgiveness. What does custodial sentences – serving an indefinite time – do to a human being? What do we as a society want to obtain with our justice systems, and the balance between punishment and rehabilitation? Womanhood, motherhood. The healing power of friendship and love.

The strength you need as an inmate, all the complex human emotions that we all have our ways of running away from, but which in prison have to be faced and lived through within the same four walls day after day, year after year.

We also hope that the film will show how we could end up behind the walls, and raise the questions of what truly shapes our life paths and choices. And if you can change your fate. I hope it will inspire us to see ourselves in our fellow human beings, and together strive for systems in which so much human potential and lives are not lost behind the walls.

In a world with so much war and big politics at the moment, we can all feel very powerless. I truly hope that the film will be a reminder of the huge importance we can all have, human to human, and the role we can play in each other’s lives.

Nina: To me, one of the strengths of this film having two directors is that I never was too focused on themes or turns or following rules. I did not want to force the film into something. In my opinion, documentary is documenting reality. Clearly I could have had a frame of questions, but then I would steer it instead of following the talk as a river. The themes and the potential of this story was first seen by Sophie. Ruth and I were not putting focus on what was happening between us. Being able to lean into the moment was also part of the authencity. Sofie could see what was happening. It is very weird to see material about yourself in such a vulnerable situation. I never thought about themes, I only thought about truth.

Nina: Is there a theme you’d like to mention now?

Sometimes it is important to go back to basics. For all human beings, the most uncomfortable feeling ever is to feel alone. We all want to be seen, and we want to be good enough, and then we might hide what makes us nuanced and individual. I hope this film can open up new questions. It is not a film about giving a lot of answers. How is your pain shaped, and how did it affect your life? You can’t have that dialogue with yourself. It has a huge impact on who you are today and what your passion is, what your ideas and visions are based on.

How would you describe the current state of documentary film, and film in general in Greenland today?

Nina: I think we are at a very beautiful stage. I’ve been in the film industry for about 15 years, and when I entered this world it was like a feeling of finding your way home. Ever since, it has been an ambition and a priority of mine to invite other lost souls to this world. Art has the ability to change pain. It is a way of describing pain, how we see ourselves and our country. Art is the foundation of everything, and there are so many creative people in Greenland who have not found their home today. There are so many inspiring stories that have not been told yet.

I’m always thinking about young people, and I think we are experiencing a slow transition or change now in how to deal with life. They have so much courage, and what you need in order to make great films is courage, especially when making documentaries. If we as the established industry can direct their courage into our world, it can take the industry to the next chapter.

CLICK HERE to read the jury's motivation for WALLS - Akinni Inuk.

All nominated films for the Nordic Council Film Prize 2025 can be watched during these upcoming events: