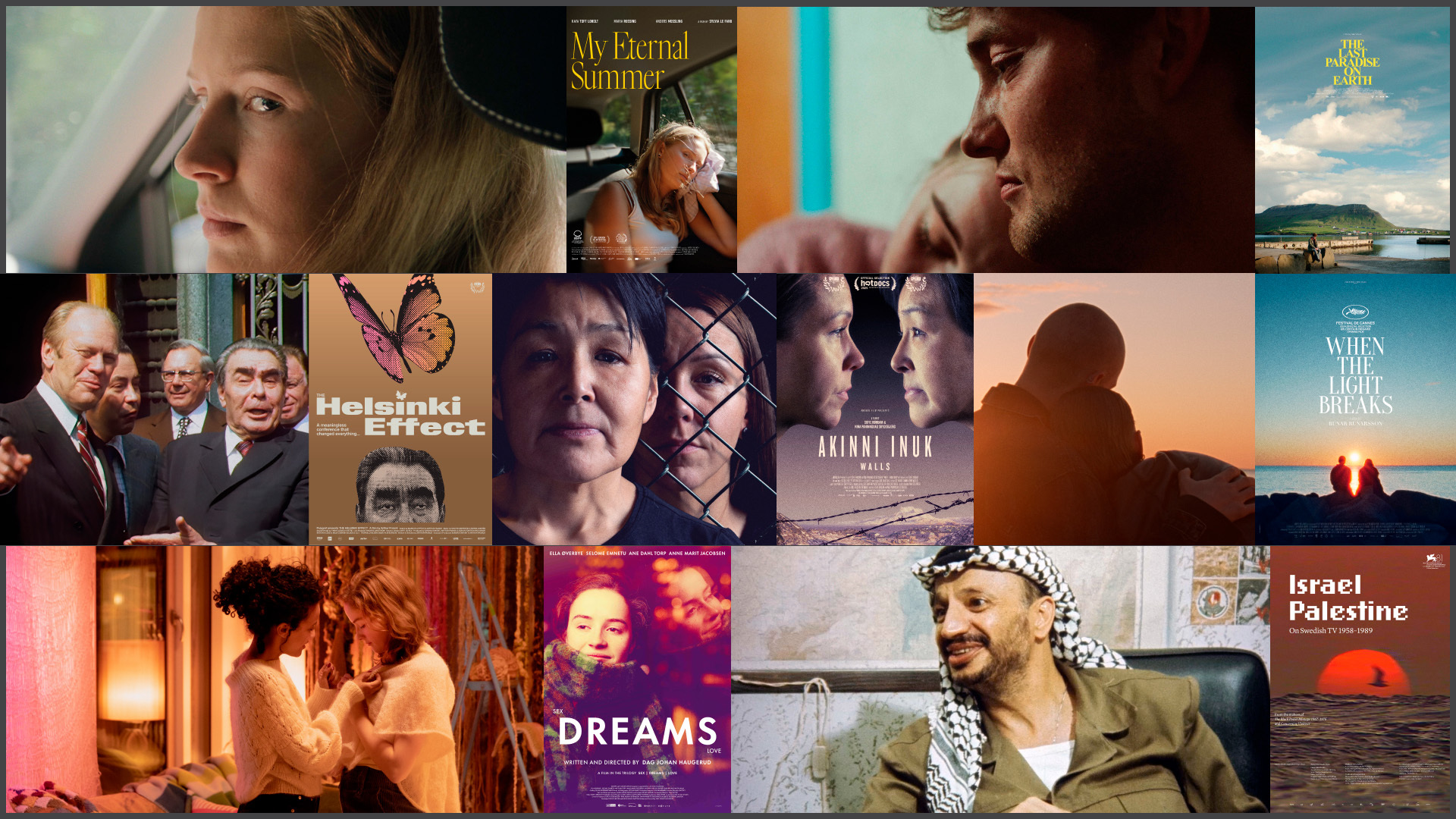

Seven exceptional films nominated for the 2025 Nordic Council Film Prize

First-ever nomination from the Faroe Islands – and a landmark year for Nordic documentaries.

Stórá says being stuck on Faroe Islands is an equivalent to teenage angst. In The Last Paradise on Earth however, he focuses more on what we have than what we long for.

The Faroese writer-director Sakaris Stórá, the writers Tommy Oksen and Mads Stegger and the producer Jón Hammer are nominated by the Faroese jury for the Nordic Council Film Prize 2025 for their feature film The Last Paradise on Earth (Seinasta paradís á jørð).

Stórá’s film revolves around Kári, who works at a fish factory in a small Faroese town named Hvalba – a setting inspired by Stórá’s own experiences from working in a factory. While the film’s protagonist Kári (Sámal H. Hansen) finds solace in his work, his sister Silja (Bjørg Brynhildardóttir Egholm) struggles to finish school. At the same time, their father is set to return to the sea after many years. When the fish factory where Kári works suddenly faces the threat of closure, the family’s fragile reality begins to unravel. As friends dream of escape and seek new lives beyond the island, Kári makes a different choice: to stay and confront life head-on.

After studying film at Nordland School of Art and Film in Lofoten, Norway, Sakaris Stórá moved back to his home town Sandoy on the Faroe Islands to make films in the Faroese language. His previous work includes Dreams by the Sea (Dreymar við havið) and the short films The Passenger (Passasjeren) and Summer Night (Summarnátt). The Last Paradise on Earth is produced by Adomeit Film (DK) and Kykmyndir (FO).

In this dialogue series we interview the directors of the seven nominated films. CLICK HERE to see all nominees.

Sakaris Stórá, what was your first impulse to make this film?

I worked in a factory, very much like the character in the film. And I wanted to capture that environment and culture. Especially since the small worker communities that live off the resources in nature are slowly disappearing. Everything I had done prior to this film, was in some sense about a longing for the bigger world out there. And with this film I wanted to explore the opposite of that. The world is changing in so many ways, not only economically and environmentally, but also socially. How distant we are becoming to each other and how we often are so focused on “being” something or achieving something, that we tend to forget to listen and to see the beauty in what we actually have.

Can you describe the creative process of writing the script together with Tommy Oksen and Mads Stegger, and then you directing it?

Yes. I wrote the first versions of the script myself, but I felt somewhat limited in the writing, because the story was on many levels very personal. I also wanted to work with someone from abroad, to make sure the story was understandable for people who might not know anything about the islands on beforehand. For every draft, we wrote the script in Danish. I translated the dialogue to Faroese, then worked on it, sometimes together with the actors, then rewrote and translated it back to Danish. It was time-consuming, but very giving. I enjoyed working with them.

You work a lot with young actors and characters. Why is that?

The stories I have worked with have mostly featured young characters. The Faroe Islands as a setting works well for that kind of stories. I think being stuck on a small group of islands in the middle of nowhere must be the geographical equivalent to some sort of teenage angst, and it resonates well with that. Maybe it also has something to do with Faroese cinema being relatively young. I remember when I moved back to the islands, I was too nervous to approach the more seasoned actors. Because I didn’t feel I knew anything about acting.

The Faroe Islands have less than 55,000 inhabitants. How did you find these very convincing actors in such a small culture?

We had auditions for the younger actors, and I had worked with Sámal Hansen and some of the other actors previously. For the character of the sister, we had less than 20 people showing up for audition. And I don’t think any of them had ever been in front of a camera before. In a bigger country we could have gotten 10 or 100 times that many, and most of them would have some schooling or acting experience. But I am so happy with the casting of the film.

I worked very closely with the lead actors, even before the final script was done. We spent a lot of time working on the chemistry between them. Both of the characters are constantly hiding their emotions, so we worked a lot with how the emotions live under the surface, and how they communicate with few words. Working with the actors, building the characters together, and seeing them grow, felt like a privilege and an honour.

In my view, there were strong themes of identity and belonging in your film. Which themes became most important for you during the process, and why?

It’s a good question, because a lot of it really happened throughout the process. I try as much as I can to see film as a living thing that almost speaks to you during the writing, rehearsals and shooting. But I have always thought the identity thing is interesting to work with, because it is, in all shapes and sizes, fundamental to every one of us. My short films revolved around sexual identity, which back then was very necessary to deal with in the Faroe Islands. But underneath that, it was very much about feeling estranged or alienated, and to come to terms with accepting who you are. It’s probably because I have always felt a bit like an outsider myself.

If there is any moral message in my films, it has to be: “It is okay to be who you are.” I think that message just becomes more and more important. With social media and all, there surely is no lack of the opposite.

What key elements were important for you when creating the film’s special tone?

For the whole team, it was important to create an honest portrayal of the characters and environment. I know “honesty” can be a bit of a buzzword, but for us, it meant things like avoiding romanticising and glamourising the factory work, and rather showing it as it is. We also insisted on using real locations, so everything was within a walking distance. Even the nature shots. We all lived in the town during production, and that was rewarding.

To get the right tone, I wanted the pace of the film to reflect both the emotional and physical pace of the main character and how he observes the bubble he lives in. I think you really feel it in the cinematography and the pace of editing. And then of course there was the whole use of music and sound, which we spent a lot of time on shaping, even during the writing of the script.

How would you describe the current state of the film industry in the Faroe Islands?

It has grown very much in the last ten years. We have talent, we are collectively getting better at it with every project that gets made, and today you could make something good with an all-local crew. So there is much potential, and it is really exciting to watch it evolve.

The political part of it is a little hard to speak about. There are reimbursements on the spending of foreign productions, so that part works well. But when it comes to the funding of local productions, it is not looking too good. The politicians are talking about the obvious importance of culture and film. But when it comes to allocating funding, the government is not really taking their role seriously. Which is a shame. But it is not stopping us from telling our stories.

Official trailer:

CLICK HERE to read the jury's motivation for The Last Paradise on Earth.

All nominated films for the Nordic Council Film Prize 2025 can be watched during the following events: