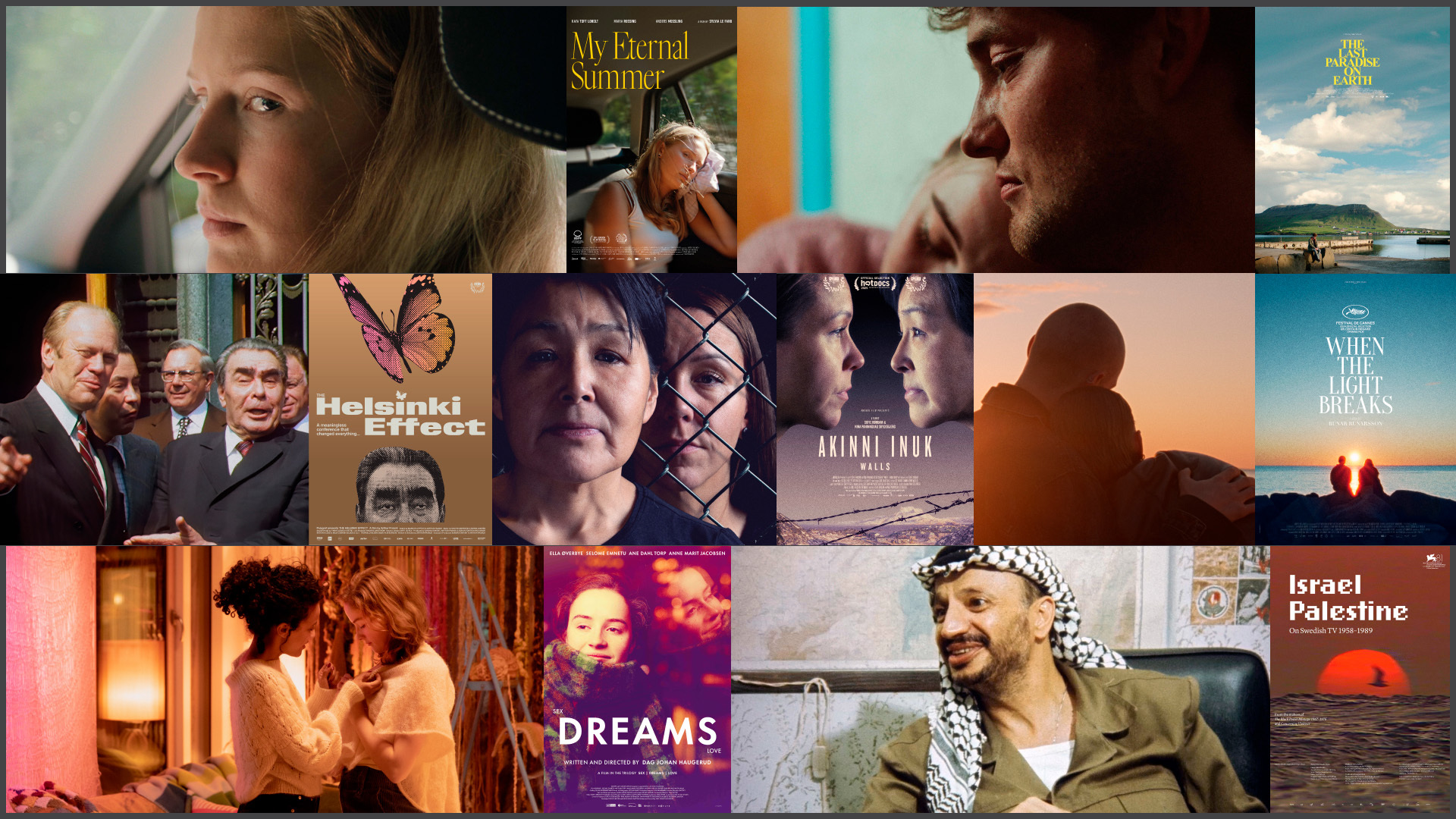

Seven exceptional films nominated for the 2025 Nordic Council Film Prize

First-ever nomination from the Faroe Islands – and a landmark year for Nordic documentaries.

The director of Israel Palestine on Swedish TV 1958–1989, Göran Hugo Olsson, who sees documentary as a method rather than a genre, says that working with the documentary gave him an insight in a painful way.

The Swedish director Göran Hugo Olsson and producer Tobias Janson are nominated by the Swedish jury for the Nordic Council Film Prize 2025 for their documentary film Israel Palestine on Swedish TV 1958-1989 (Israel Palestina på svensk TV 1958-1989).

The documentary is a cinematic account of the background to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict through immersive footage, long buried in the vaults of the Swedish Television (SVT) archives. During the years 1958 to 1989, SVT’s reporting from Israel and Palestine was unique. Their reporters were constantly present in the war-affected region, documenting everything from everyday life to international crises. News coverage with Yasser Arafat and interviews with Israeli foreign minister Abba Eban during a visit to Sweden are parts of exclusive archive material that has not been shown since first broadcast. Combined, they tell the story of a changed media landscape and give us tools to understand a conflict that has affected our time like few others.

Göran Hugo Olsson holds a degree from the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm, and has been a prominent figure on the documentary scene both in Sweden and internationally. His previous films includes Fuck you, Fuck You Very Much (1998), The Black Power Mixtape 1967-1975 (2011), and Concerning Violence (Om våld, 2014). Israel Palestine on Swedish TV 1958-1989 is produced by Story AB.

In this dialogue series we interview the directors of the seven nominated films. CLICK HERE to see all nominees.

Göran Hugo Olsson, what was the first impulse for you to make this film?

I think there are always two different factors that play in when deciding to make a film. The first is that the material, the idea, the access, and the concept of the film makes it worth doing. That it is interesting and important. Secondly, you have to ask yourself: Is there an audience for this? It doesn't have to be a huge audience, it could be a very small one. This film took five or maybe six years to do, and if you invest that amount of time in something, it has to be good, and it has to make sense to some audience. Now this film opens in America in at least four different cities. That's a huge thing, but that wasn't my idea from the start. This was supposed to be a Nordic or a Swedish film.

How did you know that this type of film and subject would be interesting to the audience?

I did make another film for SVT, and I came across some stuff about Israel-Palestine that I didn't know of, and that was really good. And I think that sparked the idea. Plus, I knew that something was going to happen in the Middle East, but I had no idea it would be on this scale, with this magnitude of suffering and violence. I remember in the first dialogue with the Swedish Film Institute or the Swedish Television, I said: “Why don't we do this film, and then you keep it and screen it when it explodes?” They looked at me like I was crazy. But that was exactly what happened.

How do you collaborate with SVT?

5 or 10 years ago I was making international films, especially in the United States. But I got really tired of doing international films, because it took so long and it was so costly, with all the rights and lawyers. I made a film called That Summer (Den Sommaren) with American material, and during that one and a half year, I was in New York 15 times. I think half of the time I just had meetings with lawyers. So I decided I wanted to do Swedish one-hour films instead. I’ve always wanted to work in television more than with film. I made two one hour television specials for Swedish Television, and I loved the fact that I could use any material and any music I would like.

But television funding in Sweden is not enough, so we have to have other funding as well. And I could honestly say that the support from the Nordisk Film & TV Fond has been pivotal in most of our films. Now we have trouble accessing that, because it's not so easy for us to get the other broadcasters in Scandinavia along. So that's very, very sad, because Nordisk Film & TV Fond has been so important for our films. If we hadn't had NFTVF, I think we would just do domestic films for a fraction of the budget, and we would never reach outside the borders of the Swedish kingdom.

You’ve made documentaries based on archival footage before. Why are you drawn to the form?

This film is archival, but I'm not an archival filmmaker. I'm a filmmaker that uses existing footage. I also made another film called The Society of the Spectacle (La société du spectacle), which is more based on YouTube and commercials and contemporary things.

And as I see it, documentary is not a genre, it’s a method. You could write a book with this method, you could do a radio thing with this method. But the thing is, you have to have a deep relationship with the object before, during, and after. And most often that connection is a relation with another human being; I know you, we were growing up together, you committed murder, and I could make a film about you because I know you from before. But I can't make a documentary film about a random person committing a murder, because we don't have a relationship. Then it's a journalistic film, and that's something different.

So this method goes hand in hand with technical development. Previously, only privileged white males could afford or have the self-commitment to travel and record documentary films. But with the technological development, making cameras that everybody could use, it makes no sense for people like me going into another community or environment to make a film. That should be done by a filmmaker from the inside. I came to this insight 10-15 years ago.

But what I could do is, I could use the material of a connection I own – the one with the Swedish Public Service. They made those programmes for me, I saw them when I was a kid, so I have the right to use them in a documentary way.

You watched around 5,000 hours of footage for this film. How did you select what to use? What did you look for?

That's a million dollar question. That's our job. That's all we do, all day and half of the night. It's impossible for us to explain, because that's all we do. That's our trade, you know. But at the same time, I don't think there is a difference in telling a story through film or telling a story verbally in a dinner conversation. All inter-human communication is the same: It's a mixture of what is important to me and what I think it's interesting to you. That's it.

What does it mean to you as a documentarist to be “objective”?

The public broadcaster doesn’t deal with the word “objective”, but with the term“non-partial”. In the broadcast permit with the government, it says that public service should be non-partial. If you do a short insert about something, for example pollution in nature, you have to portray both sides. However, if you make an insert or a film about a big topic like Israel-Palestine, you don't have to be non-partial in that specific insert, but the overall presentation should be non-partial. Nobody could be totally objective, that's impossible, but the broadcaster should all in all be non-partial. In every subject except two, at least in the Swedish broadcaster; racism and democracy.

But also during this time, the Cold War – Finland, Sweden, Austria and Switzerland were the only neutral countries in Europe. So what’s equally important in this film is that the Swedes had access to both sides in the Cold War. That’s a key into this material and it’s more important than public service being non-partial. We were definitely anti-communist, but we weren't like “It's the end of the world with some communism”. We were very critical of American commercialism and imperialism.

What did you learn from making this film?

That there will never be a Palestinian state. I watched thousands of hours of footage from this 50-year period, and the following trend after that is also very obvious. There will be Palestinians in Israel, there will be Palestinians in what we call Palestine, but the Palestinians lose every time. That’s nothing new, but I learned it the painful way.

How would you describe the current state of documentary film in Sweden today?

I think the current state of documentary in Sweden is the same as the global situation. I think that there is a default way of making films. Since documentarists are working in reservation, I think the vanity of those who make films with the ambition of getting into festivals, together with the financiers, leads them to follow a formula with music and images and drones and blah blah blah. That makes most documentaries so uninteresting.

I think the documentary format is stuck in an interfered complex that doesn't make the films legit to most audiences. People don't make documentaries for influencing other people; they make documentaries for sending them to a festival in another country than they live in themselves.

Official trailer:

CLICK HERE to read the jury's motivation for Israel Palestine on Swedish TV 1958-1989.

All nominated films for the Nordic Council Film Prize 2025 were screened during these events: