WRITTEN BY: Annika Pham

The top Swedish arthouse distribution outfit has more than 15 upcoming film releases for 2022-23 including five Cannes competition titles.

The top Swedish arthouse distribution outfit has more than 15 upcoming film releases for 2022-23 including five Cannes competition titles.

TriArt boasts a catalogue of more than 700 high quality films, including several Palme d’or winners such as Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite, Ruben Östlund’s The Square, Hirokazu Kore-eda’s Shoplifters and Jacques Audiard´s Dheepan.

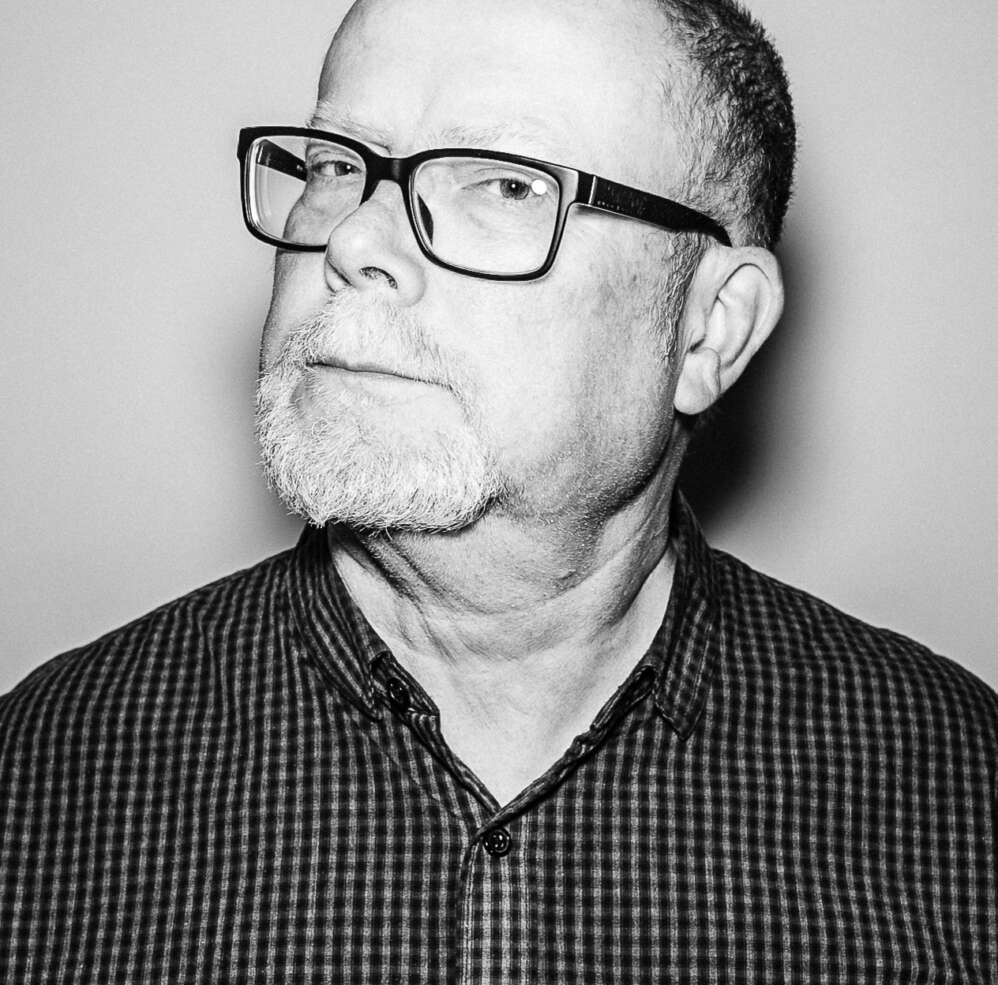

This year’s Palme d’or contenders pre-bought by TriArt’s founder and head of acquisition Mattias Nohrborg include Ali Abbasi’s Holy Spider, Tarik Saleh’s Boy from Heaven, les frères Dardenne’s Tori and Lokita, Kore’eda’s Broker and Léonor Seraille´s Mother and Son.

Ahead of the Cannes Film Festival, we spoke to the veteran Swedish buyer and producer about his strategy to navigate the turbulent times in distribution.

You have four films in competition in Cannes. When did you come on board each project?

Mattias Nohrborg: Regarding Holy Spider, we had Ali Abbasi’s previous film Border, so it was natural to board his new film. I got the film through Nordisk Film who are co-producers. With Boy from Heaven, I’ve known Tarik [Saleh] and producer Kristina Åberg a long time and I’m a big fan of Saleh’s films.

Regarding Kore-eda and the Dardenne brothers, I’ve released several of their films in the past and continue to build their brand name in Sweden. I bought both films at script stage.

With Léonor Seraille’s Mother and Son, I read the script in November last year, and started to discuss it with sales agent MK2 in Berlin in February. It’s super strong politically, very emotional, and I have a big trust in the director. I finalised the acquisition two weeks ago.

How are you approaching Cannes? Do you still have space for new acquisitions? How is your backlog of titles after the pandemic?

MN: We don’t have that many films waiting for release and during the pandemic, we actually didn’t buy a lot. The problem is more the competition on screens and arthouse films cannibalising each other. Also after Covid, the arthouse audience hasn’t really come back to the cinemas, but I hope things will loosen up.

We are entering the weakest period in theatrical distribution as traditionally Swedes don’t go that often to the movies from mid-June. We are therefore concentrating on Q4. We have another eight films to release until the end of 2022, including the Swedish films Boy from Heaven, Abbe Hassan’s Exodus, Lovisa Sirén’s Sagres, as well as Holy Spider and Broken. Our plate is almost full until May 2023, but I may buy another two or three new films in Cannes.

How many films do you release in cinemas every year, and what’s the share of Swedish films?

MN: We release around 18-20 films a year of which about 40% are Swedish or Nordic co-productions. We are the biggest distributors of arthouse Swedish films in Sweden, and enjoy long-time relationships with local producers and filmmakers. We also help the new pan-Nordic players Scandinavian Film Distribution with their physical distribution and programming in Sweden.

When it comes to foreign acquisitions, in the future we will concentrate much more on titles screening at major A-festivals. It’s tough out there, a real gamble actually. you’re not sure when and why a film will work. A big chunk of our main audience are women 40+, but that audience is very slow at coming back to the cinemas. You have to be much more careful in your choices and evaluate the risks. We’re more reluctant for instance to go with first-time directors, low budget films, and try to target bigger names, more secure bets, unless the package is extraordinary. These tougher times for arthouse foreign-language films in Sweden is reflected in acquisition prices - bigger films are still expensive but medium sized budget films are cheaper today.

What works today in Swedish cinemas? What recent successes have you had?

MN: On the foreign-language [non-US] side, we did OK with Joachim Trier’s The Worst Person in the World-around 35,000 admissions. Pre-pandemic, we would probably have reached 60,000. But the film will most likely do better on VOD, so we’ll be OK financially as we have additional rights. We had high hopes with Valdimar Jóhannsson's Lamb, but it did only 2,500 admissions, which shows how volatile the market is these days. On the other hand, we continue to have good surprises with Swedish films, including documentaries. For instance, we did 35,000 admissions with Isabell Andersson’s documentary Lena about actress Lena Nyman. Then the film I am Zlatan [released by Nordisk Film] that I produced for B-Reel Films is doing fine, with more than 215,000 admissions so far and still climbing.

How have you adapted your acquisition strategy to the changing market?

MN: I try to get more guaranties, ie as many rights as possible. If theatrical doesn’t work, we can still lower our risks by selling to television, and relying on TVOD and SVOD that are climbing. With Swedish films, we also try to secure all rights across the Nordics, including pan-Nordic SVOD rights, whether a film goes on our platform TriArt Play or other Nordic streamers. That said the theatrical is still essential as a launching pad to create a buzz.

How aggressive are you to reach the target audience where they are?

MN: Of course we rely on social media, we try to find new partnerships, organisations to reach audiences directly. Events with screenings followed by Q&As are more important than ever. They are always full.

How is the debate around windowing in Sweden?

MN: It’s still messy as the largest chain Filmstaden owned by Odeon-AMC Theatres which controls 70% of the cinema market have different rules for different distributors. They offer a holdback of 1-2 months for some players and 4 months for medium-sized indie distributors like us. For some films, it’s simply too long. We’re fighting this but have little influence.

What do you feel is needed in Sweden to help local films increase their market share at the B.O.?

MN: There is a big paradox in Sweden. We have the biggest presence ever in Cannes and great international attention, but our films struggle at home.

The problem with our domestic market share is really linked to the type of films that we produce. Arthouse quality films are thriving, we are probably the best in Scandinavia these days in this segment, and the Cannes selection proves it.

However mainstream Swedish films are the real problem. They aren’t good enough. If you deliver bad comedies, people won’t come or won’t come back. You can’t cheat the audience. We have to critically look at what we’re doing, as an industry to try to solve the issues. We have good series for a large audience, so why can’t we do very good mainstream films for the cinemas? I am Zlatan is doing fine -although it would have done easily 2-3 times its current admissions pre-pandemic. But I believe this is the type of quality mainstream film that the audience is craving for.